The Dominance of Mandarin

Mandarin Chinese reigns supreme as the primary language used throughout Taiwan. According to the most recent census data, over 70% of Taiwanese citizens report Mandarin as their primary language. This is in stark contrast to just a few decades ago when other varieties like Taiwanese Hokkien held much more prominence, especially in southern Taiwan. The shift toward Mandarin can be attributed to several key political and social factors over the 20th century. When the Kuomintang (KMT) government retreated to Taiwan after losing the Chinese Civil War, they embarked on a Sinification campaign. This involved promoting Standard Mandarin Chinese and downplaying local varieties to foster a sense of shared Chinese identity and culture across Taiwan. Mandarin was established as the primary language of education, government, and media―greatly aiding its spread throughout Taiwanese society. Younger generations in particular have been brought up learning exclusively in Mandarin classrooms.

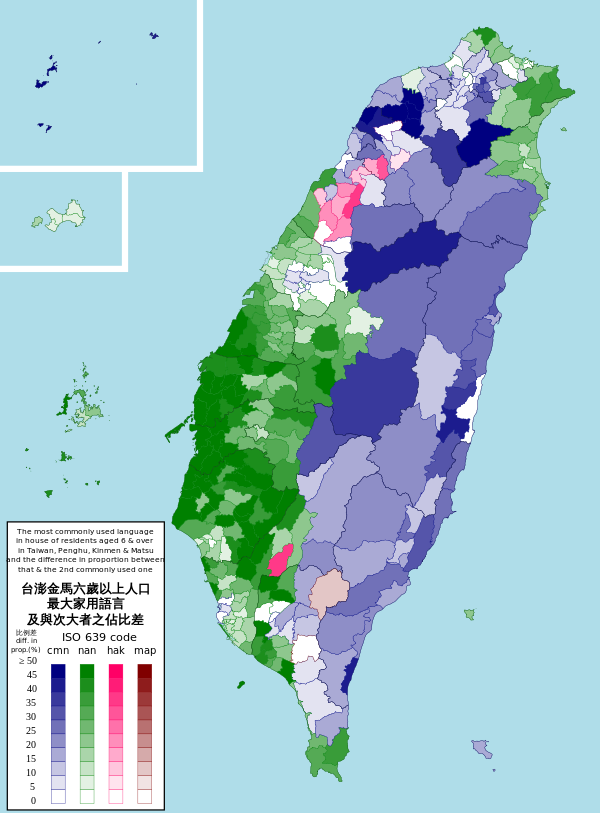

Regional Variations in Language Usage

While Mandarin is by far the most dominant language nationally, significant regional variations still exist in language preferences and abilities across Taiwan. Hokkien remains most strongly linked to identity in southern Taiwan where over 50% still report it as their primary language. Areas like Tainan and Kaohsiung have lively night markets where Hokkien dialects can be heard frequently. Further north in cities like Taipei, Mandarin is essentially the sole language in use by the general public. The indigenous peoples also maintain over a dozen unique languages like Amis, Paiwan, and Bunun that are endangered but efforts are being made to revive cultural heritage. On Orchid Island, close to 60% of the population still speaks the native Tao language. Meanwhile in Hakka populated regions, their distinct variety maintains a presence too despite facing assimilation pressures over the decades.

Hokkien: From Lingua Franca to Endangered Dialect

At one point, Taiwanese Hokkien served as a common lingua franca across Taiwan due to widespread migration from southern Fujian province in mainland China. This variety became firmly established as the language of daily life even in areas like Taipei. However, its stature and transmission has sharply declined as Mandarin has ascended to become viewed as more politically and economically advantageous. Now Hokkien faces extinction as younger, urbanized Taiwanese almost never acquire it as more than a passive understanding. A lack of institutional support and domains of active usage have severely impacted intergenerational transmission. While still spoken by over 60% of elders, less than 10% of Taiwanese under 40 regard themselves as fluent. Revival efforts stressing cultural significance have had limited success against such formidable forces of language shift towards Mandarin. Scholars warn that without drastic intervention, Hokkien might disappear within a few generations as its elderly native speakers pass on. This would represent a major loss of linguistic diversity and intangible cultural heritage for Taiwan. Initiatives promoting Hokkien in schools, media, and the creative industries have been proposed to help revitalize interest and reverse this decline.

Bilingualism and Multilingual Taiwan

While language shifts are threatening some minority tongues, Taiwan has also cultivated a reputation as one of Asia’s most bilingual and multilingual societies. This stems both from its complex linguistic history as well as forward-thinking language policies pursued by the government. According to a 2016 census, over half of Taiwanese report the ability to communicate in two or more languages including Mandarin, English, and various Formosan languages. The population’s high levels of English proficiency in particular have stemmed from its emphasis on English education starting from primary levels. This provides Taiwanese with access to international opportunities and global connectivity. Meanwhile younger generations often mix languages casually in daily code-switching between Mandarin, English, and Hokkien terms. Multilingual signage is also very commonplace. Government efforts to teach and promote indigenous tongues have had partial success reviving threatened Formosan languages among ethnic communities and the general public. Overall Taiwan demonstrates how linguistic diversity can be both protected and enabled to flourish through forward-thinking policies valuing multilingualism.

Future Prospects: Ensuring Language Vitality

Looking ahead, Taiwan faces ongoing challenges regarding the vitality and transmission of its many languages. While Mandarin’s dominance is secure national, questions loom over Hokkien and the native Formosan tongues. Their long term prospects will hinge on policies that revive usage domains and instill positive associations with youth.

Efforts bringing languages into education, media, arts/culture and the tech sphere could reinvigorate intergenerational transmission while cultivating new domains of natural active usage. Community advocacy and identity building initiatives will also be key to ensuring languages’ resilience against assimilation pressures. International experiences point to the importance of recognizing and elevating minority languages within nation branding and soft power strategies as well.

If handled thoughtfully and inclusively, language policy in Taiwan need not entail a “zero sum” relationship between languages. Rather, with careful nurturing many flourish together reflecting the nation’s unique diversity of voice. By valuing multilingualism, future generations too may enjoy Taiwan’s rich linguistic heritage for years to come.

Mecca: A Spiritual Home to Iconic Islamic Landmarks

Mecca: A Spiritual Home to Iconic Islamic Landmarks